EHSC’s new documentary follows domestic workers as they organize for workplace protections during the COVID-19 pandemic

By Jennifer Biddle

Women, domestic work & COVID-19

Some 325,000 domestic workers labor as nannies, house cleaners and caregivers for the young, infirm, elderly and disabled in 2 million homes across California. Domestic workers are a godsend to the working parents who rely on them to support their households, helping them thrive in their own careers. But to many Americans, domestic workers live out their lives on mute and invisible, even to those who employ them.

Domestic work as “women’s work” is marginalized and undervalued, especially for women of color. At $10.79 an hour, the typical domestic worker in California makes half the median hourly wage of other workers. They’re also three times as likely to live in poverty than workers with similar jobs, according to national statistics.

Yet, domestic work has always been central to the healthy functioning of society. During the early days of the pandemic, many women took note as they juggled paid work with unpaid household chores, childcare and homeschooling, all under the same roof.

Shocks like that can create cracks in what’s “normal,” opening up space for change. COVID was just such a moment, altering experiences and expectations for everyone, including the perceptions women and workers more generally had of themselves and their place in society.

Silent no more

It might be a surprise to some Americans to know that the laws and policies governing wages and hours, health and safety and the right to organize for the most part don’t apply to domestic workers. Like other frontline employees during the COVID-19 pandemic, domestic workers risked illness and death every time they clocked in. Unlike most other workers, however, domestic employees didn’t have health and safety protections on the job.

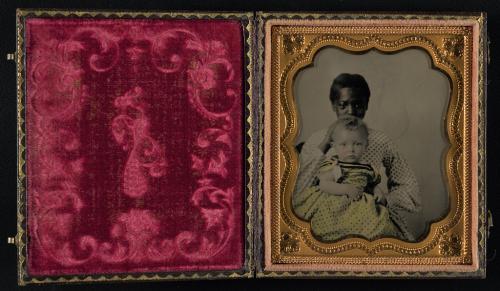

For women, the lack of protections for domestic work has always gone hand-in-hand with the notion that the home is a private space. The exclusion surfaced for unpaid labor on plantations during slavery, then reemerged in the 1930s when New Dealers and Southern lawmakers made a pact granting protections to all but domestic and agricultural workers, who at the time were mostly Black.

Unsurprisingly, not having on-the-job health and safety regulations during the pandemic was a catastrophe for California’s domestic workers. A large majority were not given masks, required to socially distance or provided COVID risk information when they entered their workplaces. Domestic workers in California were three times as likely to get COVID-19 compared with the state’s general population, according to research at UC Davis.

The marginalization of female workers, intentional exclusion of domestic work from workplace policy and the economics of COVID compounded the impact of each. Just one in five domestic workers received health insurance coverage through a job and most lacked paid leave when they got sick. On top of that, 36 percent lost all work and almost half lost some, exacting a brutal financial toll on an already vulnerable population.

As dire as all that sounds, COVID simultaneously changed attitudes toward work during the pandemic. The economic and social need for essential workers to keep working during a global public health crisis, and the risks in doing so, came together to galvanize California’s domestic workforce to change the status quo.

With the help of California Senator María Elena Durazo (D, District 24), domestic workers crafted legislation that would finally bring them under Occupational Health and Safety Act (OSHA) standards. Through mass Zoom rallies and lobby days, masked protests at the State Capitol, petitions to Governor Newsom, prayer vigils and other tactics, domestic workers built a vibrant, inspired protest movement that went from silent to loud and clear.

Domestic workers today

In California today, domestic workers are mostly immigrant women. Like so many before them, they have come to this country to build a better life for themselves and their families, often fleeing other calamities like war, domestic violence or authoritarian oppression.

These new immigrants tend to work the same low wage jobs as others coming from similar circumstances. They are highly vulnerable: Since they don’t know their rights or where to get help, they face excruciatingly long hours, abuse, wage theft, rape or worse.

To highlight the health risks these workers faced during the pandemic, the UC Davis Environmental Health Sciences Center (EHSC) conducted a domestic worker research project and produced the documentary “Dignidad: California Domestic Workers’ Journey for Justice.” The film touches on the initial findings of the research and chronicles domestic workers’ efforts to pass the Health and Safety for All Workers Act (SB321).

“Domestic workers lack virtually any protections from arbitrary and unsafe working conditions,” says EHSC Director Dr. Irva Hertz-Picciotto, who led the research project and was “Dignidad’s” Executive Producer. “This film highlights their struggle to achieve dignity, respect and safe and humane working environments before and throughout the unprecedented COVID public health crisis.”

In the film, Director Paige Bierma masterfully weaves together the lives of several domestic workers who emigrated to the US from Guatemala, Mexico and the Philippines. Watching these immigrant workers discover the power they have together as they forge a community through mutual aid, solidarity and activism—at a time when the rest of society feels like it’s falling apart—is nothing short of a revelation.

“It was incredibly inspiring to work on this film with so many brave domestic workers, and especially interesting to be able to capture the ups and downs of a grassroots political movement during the uncertain times of a pandemic,” says Bierma. “I hope this film helps to show the kind of dedication and perseverance it takes to bring about real political change in this country.”

Jennifer Biddle produced “Dignidad” and “Waking Up to Wildfires” for the UC Davis Environmental Health Sciences Center. She now leads digital strategy against Big Tobacco for the California Department of Public Health.

Dignidad in the News

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences - Documentary Film Features Research and Advocacy for Domestic Worker Health and Safety | March, 2023

- The Machine Guard (a Blog of Worksafe) - Worksafe attends “Dignidad: Domestic Workers’ Journey for Justice in California” screening in the Mission | Feb 21, 2023

- The Cal Aggie - New UC Davis Environmental Health Sciences Center documentary airs on PBS | Feb 13, 2023

- California Coalition of Domestic Workers - Local Activists Host community Screening of "Dignidad: California Domestic Workers' Journey for Justice" | Feb 9, 2023

- Mission Local - Documentary on domestic workers will screen at the Brava Theater | Feb 2, 2023

- UC Davis Health - New UC Davis documentary set to air on PBS | Jan 12, 2023

- The James Irvine Foundation - Domestic Workers: A Movement for Fairness and Dignity | Oct 19, 2022