National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine Wildfire Workshop

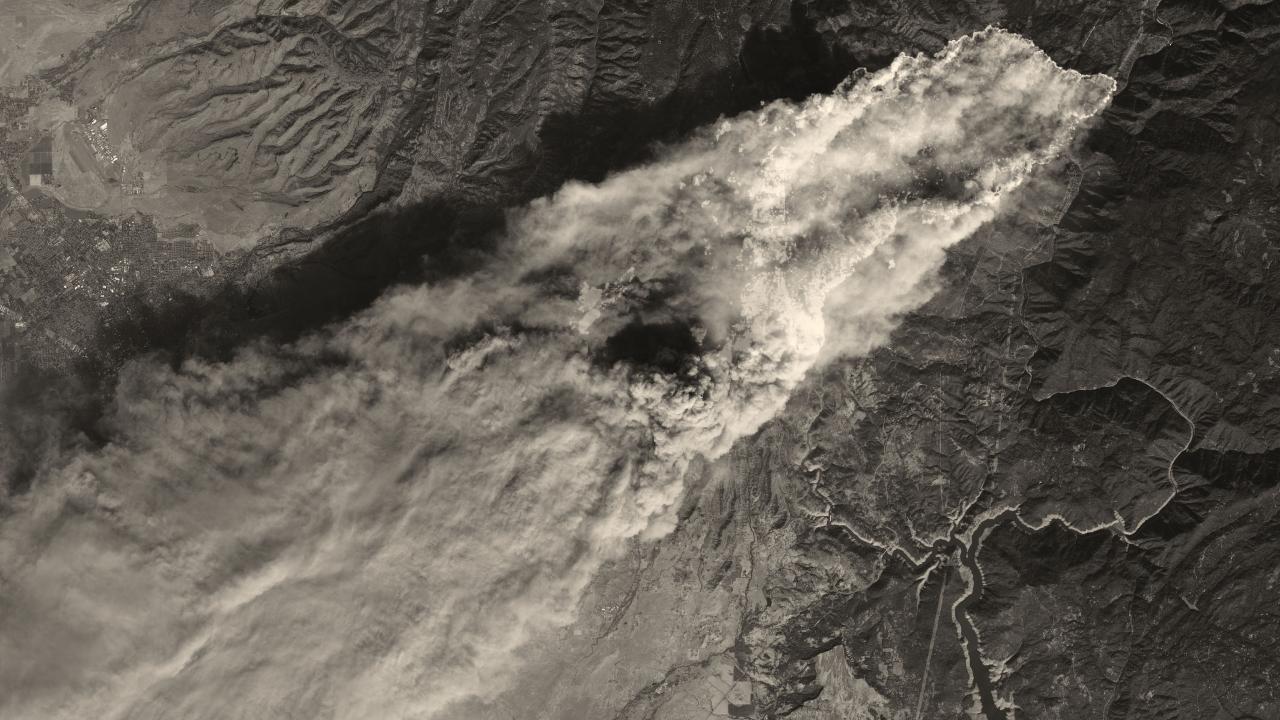

Burning down the house: Wildfires and California’s potential to remake itself

Quick Summary

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) Wildfire Workshop drew experts from across the country to California's Capitol to explore the state's future as it braced for another wildfire season.

- Researchers from the UC Davis Environmental Health Sciences Center spoke on various panels.

- Clips from our documentary Waking Up to Wildfires introduced panels throughout the event, highlighting the experiences of communities and wildfire survivors.

Summer is here and hot with the possibility of another record-breaking wildfire season in California. So for the first time ever, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) brought together experts from universities, community organizations and government agencies across the nation to discuss the future of the Golden State and other regions in the West threatened by wildfires.

The workshop, “Implications of the California wildfires for health, communities and preparedness”, will likely go down as a seminal moment for scientists and other experts beginning to grapple with the effects climate change is having on communities globally. The 2-day gathering took place at the UC Davis Medical Center in June with hundreds attending or watching via webcast, and showcased clips throughout from the UC Davis Environmental Health Sciences Center’s (EHSC) documentary Waking Up to Wildfires.

The workshop tied wildfire risks and health impacts to the weaknesses, challenges and limitations of research and community preparedness. Below are our favorite workshop highlights. If you’d like to see it all, you can watch the archived NASEM webcast online.

Rethinking our environment

The consensus is that about half the change in fire severity is being driven by climate.—Benjamin Houlton, Director, UC Davis John Muir Institute of the Environment

A pandemic is the worldwide spread of a disease: Could climate change be our planet’s next pandemic? Benjamin Houlton, professor, Chancellor’s fellow and director of the John Muir Institute of the Environment at UC Davis asked that very question.

As temperatures rise, natural disasters are getting more destructive and deadly for millions of people across the globe. Californians have experienced this devastation firsthand as wildfires burn longer and hotter year-over-year, forcing millions across the state to breathe unhealthy air.

As temperatures rise, natural disasters are getting more destructive and deadly for millions of people across the globe. Californians have experienced this devastation firsthand as wildfires burn longer and hotter year-over-year, forcing millions across the state to breathe unhealthy air.

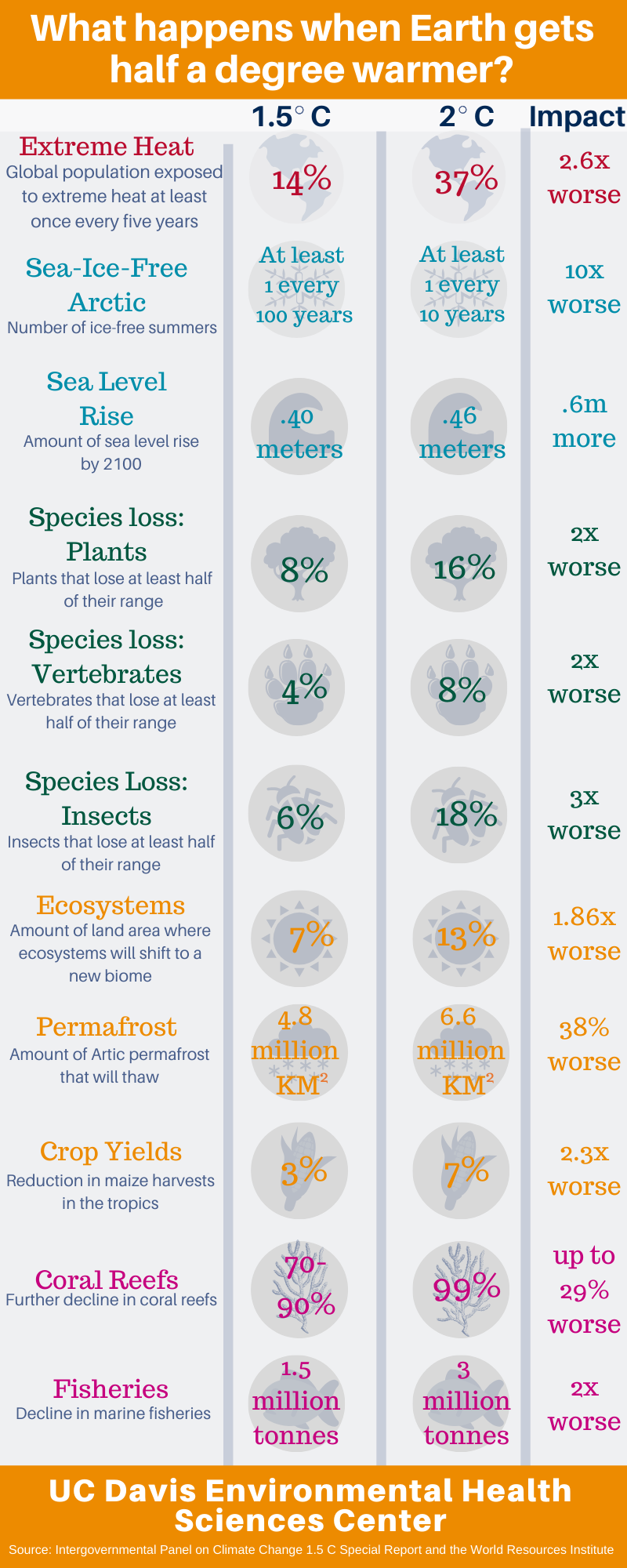

Research shows that global warming has increased the Earth's temperature roughly 1 degree Celsius (C) and that it’s expected to rise another half a degree in this half of the century. But what most people don’t realize is that 1 degree C is the global average, which Houlton says California has already surpassed.

To many people, a rise of 1.5 degrees C may not seem like much. But according to research by Houlton, Sacramento's climate in the latter half of this century is predicted to resemble Phoenix’s today. That means Sacramento will see over 40 days per year with temperatures above 104 degrees Farenheit compared with the four days per year it has now.

In addition to more wildfires, smoke and bad air, higher temperatures come with the likeliness of heat-related illnesses affecting more people. Heat stroke happens when excess heat overwhelms the body’s heat-regulating system and is the most severe form of heat illness.

From 1979 to 2014, over 9,000 people in the United States died from heat-related causes. As climate change worsens, experts predict millions will die around the world prematurely through 2050 from heat stroke or other heat-related ailments.

What the future may look like

- Climate models show Californians will see a 77 percent increase in mean wildfire burned areas by the end of the century, making early mega-wildfires like the Camp Fire seem small. Extreme wildfires also will start to appear with 50 percent more frequency.

- California will be less green and more golden. Global warming is changing our physical environment, with climate models showing grasses replacing trees across California due to wildfire activity. According to Houlton, this is the environment self-correcting, as grasslands make better carbon sinks.

Disasters bring chaos then opportunity

Community advocates say wildfires don’t discriminate but how people respond to them do. Vulnerable populations like Latinos, the elderly and people with fewer financial resources can find themselves completely left out of the recovery process.

At the NASEM workshop, Genevieve Flores-Haro, the associate director of the Mixteco/Indigena Community Organizing Project (MICOP), discussed the response and recovery during the 2017 Thomas Fire. At the time, the Thomas Fire was the largest wildfire in California to date, affecting Santa Barbara and Ventura counties.

Both counties had white, wealthy homeowners and a lower income, largely Latino population. The high levels of racial and economic disparities existing in these counties already has had a big impact during the fire and afterward. Who received help and who didn’t was dependent on who controlled the narrative – and that was mostly homeowners, according to Flores-Haro.

Many immigrants simply couldn’t afford to evacuate and were left behind. On “The Avenue,” a predominantly working class, immigrant neighborhood in Ventura, 80 percent of residents didn’t have the money to leave.

These immigrants may not have lost a home, but they suffered from the fire in other ways. Flores-Haro said her organization saw many survivors whose health was seriously affected.

Part of the problem Flores-Haro said was that it took 10 days for the counties to release wildfire-related information in Spanish, and even longer to translate it into the indigenous Mixteco language used by many immigrants. (Mixteco is 3,000 years old, pre-dating Spanish and sounding nothing like it.)

With 24,000 Mixtecs living in Ventura County alone, these residents didn’t have the most basic safety information – like advisory boil and evacuation orders. Flores-Haro played a social media video her organization created in Mixteco about air quality and the importance of wearing an N-95 mask, to show how different the language sounded and how her group got the word out.

“We’re not a disaster relief organization,” Flores-Haro said, “But when the Thomas Fire hit, that’s what we became,”

What the future may look like

- Community organizations like Flores-Haro’s are supporting protections for outdoor workers during wildfires. CalOSHA recently approved an emergency regulation ensuring all employers provide N95 masks to outdoor workers when the air is unhealthy to breathe. At UC Davis, the Western Center for Agricultural Health and Safety will be studying the effectiveness of this regulation and how it’s being implemented for farmworkers.

- AB1877 passed recently to ensure emergency notifications are translated into the most commonly spoken language other than English in future disasters.

- UndocuFunds are filling a critical service gap for undocumented immigrants in the wake of disasters. The Santa Rosa UndocuFund provided immediate relief for survivors of the 2017 North Bay wildfires, and was the model MICOP used to set up their own UndocuFund after the Thomas Fire.

Reshaping our communities

When you lose an entire community you can say: How would we like our community to look in the future? Andy Miller, MD, Health Officer, Butte County

Directly and indirectly, wildfires are reshaping whole communities and having a profound impact on surrounding cities and towns too, said Andy Miller, MD, the Butte County public health officer who spoke about his experiences during the Camp Fire.

Fifty thousand people evacuated during the Camp Fire and almost all of them landed in nearby Chico, a town of only 93,000. That meant 15 years of projected growth occurred overnight.

This refugee crisis impacted shelters, hospitals and services way beyond their capacities. There was an immediate increase of 1 million gallons of sewage per day. Traffic increased by 25 percent in Chico overall and 77 percent in its main thoroughfares. Miller said seemingly simple things like getting life-saving prescription refills quickly became problematic as local pharmacies were totally overwhelmed.

In addition to vacant housing being nonexistent, some 10,000 animals also needed shelter and care, which a small staff in the Butte County Department of Public Health had to organize and manage for months on end.

What the future may look like

- PG&E recently announced all power lines in Paradise will be rebuilt underground.

- The city is also discussing how to rebuild affordable housing after losing 30 mobile home parks in the Camp Fire, as well as construct fire breaks with green belts and additional evacuation routes.

How we transfer health risks

Something that takes place very early on in life can have long-lasting and profound effects on the respiratory system as well as the immune system.—Lisa Miller, Professor, Department of Anatomy, Physiology, and Cell Biology, UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine

Although urban wildfires are a new concern for researchers, smoke from wildfires that burn vegetation are known to be harmful. While scientists have established what’s in this type of wildfire smoke, they’re still studying how it harms humans.

Lisa Miller, a professor at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, uses primate models to assess the impact wildfire smoke from burning vegetation has on long-term health. During the 2008 Trinity-Humboldt wildfires, outdoor infant monkeys at the California National Primate Research Center were exposed to wildfire smoke emissions. Miller followed the infant monkeys exposed at one to three months of age for eight years to find out if a short-term, acute exposure could have a long-term impact on their health. What she learned was remarkable:

- At 3 years old, adolescent monkeys had significantly reduced lung volume, a suppressed immune system and reduced lung stretch (or a very stiff lung). There were no signs of asthma.

- At 8 years old, adult female monkeys continued to have an impaired immune system. They also had a significantly reduced lung volume, as well as structural changes to their lungs. These changes included increased airway radius and blood vessel density.

What the future may look like

- Miller is focusing her current research on female monkeys to see if they pass on health impacts to their offspring. Results haven’t been published yet, but Miller says her research shows babies of females exposed to smoke during infancy also have an impaired immune system.

Firefighters face trauma and health problems, too

What’s firefighter versus public exposure? If we don't want smoke in our air and we're asking firefighters to suppress it, how are we transferring risk and what does it look like? Kathleen Navarro, wildland firefighter and forest planning specialist, US Forest Service

Kathleen Navarro, forest planning specialist for the US Forest Service and a wildland firefighter who took a break from an interagency hotshot crew in Oregon to present at the NASEM workshop, researches the effects wildfire smoke has on wildland firefighters.

Wildland firefighters work 16-hour days and wear no respiratory protection. They’re exposed to volatile organic compounds, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, particulate matter, CO and CO2 through the smoke they inhale all day, day after day, and even in their off hours while they’re at base camp, which is typically situated close to the wildfire.

Reviewing the scientific literature, Navarro pointed to a host of health problems related to firefighting, including: decreased lung function and increased blood pressure, arrhythmia, knee surgery, inflammation, airway response (a characteristic of asthma) and respiratory symptoms. Research also has shown that crew type and training plays a role in exposure levels.

Navarro’s own research examined dose of particulate matter (PM4) to understand the long-term risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease (CVD). For wildland firefighters working 500 hours of overtime over 5 years, excess risk was 8 percent for lung cancer and 16 percent for CVD. For firefighters working 1,000 hours of overtime in a career spanning 25 years, excess risk was 43 percent for lung cancer and 30 percent for CVD.

What the future may look like

- Many firefighters have misperceptions about the safety of their jobs and think smoke from the wildland isn’t as harmful as smoke from a burning building, according to Navarro. Shifting the culture so wildland firefighters protect themselves and developing occupational exposure limits will be key in keeping first responders healthy in the future.

What are the long-term health effects of breathing smoke every year? Our idea of an acute event is now episodic. The line between acute and chronic is getting blurred.—Irva Hertz-Picciotto, Director, UC Davis Environmental Health Sciences Center

Wildfires and the long-term impacts

Epidemiologist and UC Davis Environmental Health Sciences Center Director Irva Hertz-Picciotto spoke about her California wildfire research, which involved an online survey and collecting air, ash and biological samples from survivors of the 2017 North Bay wildfires. Hertz-Picciotto said she couldn’t find any papers looking at long-term health outcomes of exposure to wildfires, which is why she wanted to launch a study.

Hertz-Picciotto’s study is ongoing and has been investigating unmet needs during the disaster, as well as long-term physical and mental health outcomes. She said few research studies have looked at both mental and physical health, whether having one problem might influence the other or how socioeconomic factors play into health consequences.

Hertz-Picciotto shared a few key insights from the data she collected through the survey. Among them were that socioeconomic factors, age and sex affected health outcomes. Also, people with preexisting asthma were an especially vulnerable group during a wildfire and far more likely to have an asthma attack, bronchitis or wheezing. Also, some who never had asthma before reported asthma-like symptoms, too.

And when it came to mental health, a sizable number reported changes in level of anxiety, trouble sleeping or depressed mood — with evacuees more likely to experience these upsets.

What the future may look like

- Hertz-Picciotto is now conducting a statewide wildfire survey which any California resident can take online and will help tease out what the cumulative health impacts are over the long-term. The statewide wildfire survey is open to anyone who’s 18 or older and has been directly or indirectly affected by wildfires in California since 2017.

- The B-SAFE Study is researching the impact wildfires have during pregnancy on women and their babies. This study builds on Lisa Miller’s research by investigating how wildfires affect health in a human population.

How to live with wildfires

Local folks need to stand up when assistance stands down.—Annie Schmidt, Policy and Partnerships Director, Washington State Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network

“We can and should live with wildland fire,” said Annie Schmidt, the strategic advisor for the Washington State Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network, summarizing the National Wildland Fire Cohesive Strategy.

Schmidt discussed how this approach has played out in Washington state. In 2014, Washington recorded its most fires ever, burning 425,000 acres and sustaining $182 million in fire suppression costs alone. Then 2015 came along and wildfire destruction was significantly worse, burning over 1 million acres.

One problem has been that recovering from a wildfire takes years. Schmidt said that short-term wildfire costs make up only a fraction of the total, where long-term costs make up more than half. The burden of those long-term costs falls on state and local communities, not the federal government which absorbs only 12 percent of it.

“Recovery in this context can be challenging,” Schmidt said, “but it gives us tremendous opportunities.”

What the future may look like

- The Fire Adapted Communities Network developed a cyclical model to help survivors across the state understand wildfire adaptation better. Schmidt said the reason they did this was because individual communities rarely were in the same place at the same time. In wildfire country, understanding that preparedness, recovery and adaptation is constant helps pinpoint each community’s needs better before, during and after a wildfire.

Minding the gaps in research and health policy

John Balmes, Director of the Joint Medical Program in Environmental Health Sciences at UC Berkeley, highlighted data and policy gaps. Some of the questions he raised were:

- How can we recommend N95 masks when they don’t work well for children?

- Is the Air Quality Index the right metric to measure wildfire smoke when sensors are constructed so they read higher than they should, pick up ozone levels if it’s warm and calculate estimates over a 24-hour period?

- How can we make portable HEPA filters – which are effective – more affordable?

- Why is wildfire policy conflicting?

To illustrate the inconsistencies, Balmes mentioned that the City of Sacramento gave away N95 masks during the Camp Fire, while the Sacramento County Health Department advised against using them. The County said the masks provided a false sense of protection and may be unsafe for people with health problems. Balmes disputed the latter saying the masks weren’t much of a risk for people with health issues.

What the future may look like

- Social media is playing an increasingly central role in getting emergency and health messaging out during wildfires. Research shows that platforms like Twitter can help with disease surveillance and management during a wildfire and survivors prefer this type of personal communication over standard public service announcements.

Preparing for trauma

We need another set of tools because once you’ve encountered the hazard, it’s too late to redesign the boat.—Merrit Schrieber, Director, Psychological Programs in Emergency Medicine, UC Irvine School of Medicine

Merrit Schrieber, Director of Psychological Programs in Emergency Medicine at UC Irvine, stressed needing to identify people with the potential for chronic mental health problems more quickly. When it comes to mental health after a wildfire, Schrieber said there were many potential trajectories but the main ones were resilience and chronic dysfunction.

According to Schrieber, some 30 to 40 percent of disaster survivors and 10 to 20 percent of first responders develop some sort of new mental health disorder, like post-traumatic stress disorder or depression. But it’s the 50 to 90 percent of survivors that are critical to reach who develop what’s called a “transitory distress response.” These survivors have symptoms like insomnia or fear of a repeat event and constitute a high-risk subset.

Schrieber said mental health professionals can help reduce or prevent a chronic problem from developing in people like this – if they get treatment within 30 days.

Children are the highest risk group for mental health problems. One study after Hurricane Katrina found that 37 percent of children had a new mental health diagnosis 2 to 5 years later. Yet evidence-based, psychological first aid immediately after a trauma can go a long way: Just four hours of intervention yielded four years of significant, clinical improvement according to one Australian study.

What the future may look like

- Tools like telemedicine and computer-based therapies are easily accessible and effective, but it’s difficult to identify those most at risk in the middle of an emergency situation like a wildfire. PSYStart Rapid Mental Health Triage System is designed for just that. PSYStart can be deployed by non-mental health workers or responders to pinpoint those at risk of developing mental health problems so they can get treatment sooner than later.

Improving infrastructure

Hospitals are lean and not set up for disasters. One burn over 20 percent stresses most hospital ERs.—Tina Palmieri, MD, Director of the UC Davis Regional Burn Center

Tina Palmieri, MD is the director of the UC Davis Regional Burn Center and a burn triage expert who was the triage officer for the Tubbs and Camp fires.

The incidence of burn disasters globally has increased significantly since 1990, and in some countries like the United States and Australia, that increase is related to wildfires. Palmieri said we’re prepared for this increase in wildfires in some ways, but in other ways we’re not.

Disaster guidelines, regional disaster teams and tools like disaster triage tables help, but there’s also a serious lack of training and knowledge about burns, not enough quick transportation to burn centers and hospitals that aren’t staffed to handle the influx of serious injuries that come with wildfires.

The result is that medical mistakes happen, which have a cascading effect on the ability to treat burns. Non-burn providers estimating the size of a burn get it wrong 20 percent of the time. With that kind of error, Dr. Palmieri asked, how can providers estimate supply requirements adequately?

What the future may look like

- There’s a serious need to expand the number of burn centers nationally: There are only 123 burn centers in the nation and fewer than 1,800 beds, with 85 percent typically already occupied. Mostly concentrated in the East and West, some states don’t have any burn centers. Only four beds were available in all of Northern California and 53 across the entire state during the Camp Fire. Any large-scale disaster could easily overwhelm the country’s ability to treat its burn victims.

- Building more burn centers could help train medical professionals by giving them exposure to burn patients. Right now, burns aren’t part of the required training for general surgeons, but with more centers that could change.

Learning from the past

Don’t think of this as a wildfire problem. This is a homes and infrastructure burning problem.—David Shew, Consultant, Wildfire Defense Works

David Shew is an architect, a former wildland firefighter and a consultant for Wildfire Defense Works, the company he founded after retiring from Cal Fire. His expertise in land planning and vegetation, wildfire mapping and data analysis, community preparedness and structural engineering is helping government agencies and communities as they learn to live with wildfires. Shew says because of their complex nature, there’s no one single solution to the growing threat of wildfires.

Fifteen of the largest wildfires in California’s history have occurred since 2000, and 10 of the top 20 have happened in the last four years. Eighty to 90 percent of all structures wildfires damage or destroy are the result of embers, so building resilient homes and communities is where people need to focus their efforts, according to Shew.

Some communities are leading the way. Because the historic footprint of a fire tends to remain the same, there’s an opportunity to learn from the past. The Camp Fire’s footprint in 2018 was essentially the same as it was when a wildfire ravaged the area in 2008. This time, Paradise had a community evacuation plan in place, which Shew said probably helped to save many lives.

On the other hand, elected officials in Santa Rosa chose not to regulate the rebuilding of Coffey Park, a neighborhood razed by the 2017 Tubbs Fire, which burned a path eerily similar to the 1964 Hanly Fire. As a result, homes are once again not fire safe, according to Shew.

Shew made a plug for the National Fire Protection Association’s Firewise program, in which some 200 California communities participate. The program teaches people how to adapt to live more harmoniously with wildfires.

Over the last six years, there’s been a major shift and people recognize what we’re doing is not working. Recognition of that, can lead to change. We have to be thinking about our whole system: How do we want to live in our communities? How do we want to be in our environment?—Michelle Medley-Daniel, Deputy Director, Fire Adapted Communities Network

Michelle Medley-Daniel, the deputy director of the Watershed Center and co-director of the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network, talked about how her town of Hayfork, California transitioned from a logging town to a town living sustainably with wildfires.

She said 2015 was a wake-up call when wildfires forced her community indoors for about a month. She realized that seeing wildfires as the enemy by always extinguishing them just “passed the buck” to the future, but accepting them as part of a natural environmental process that helped the ecosystem thrive, her community could mitigate the impacts. To do this, they needed to accept a process of adaptation before, during and after a wildfire.

One of the most important things they did was to connect with other wildfire-prone communities via the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network. They also worked with TREX to train locals to help with fire management.

What the future may look like

The ways communities have lived in sync with the environment in the past can help guide us into the future. Native Americans have long lived sustainably with wildfire. The Indigenous Peoples Burning Network helps to keep those traditional practices alive by passing along tribal knowledge to improve the land’s resilience and reduce potential fire hazards. Other ways people can live more harmoniously with wildfires include:

- Having tight-knit communities that co-manage fire and landscapes

- Knowing how fire behaves in the landscape

- Intergenerational learning

- Value-based planning to map what different groups care about most to show where there’s common ground and help gather and honor existing local knowledge.

Jennifer Biddle is a digital strategist for the UC Davis Environmental Health Sciences Center. She produced the documentary Waking Up to Wildfires, which aired on PBS and received an Emmy nomination.

Maddie Hunt is a former editorial assistant and budding science writer for the Environmental Health Sciences Center at UC Davis. She is a recent UC Davis graduate, with a Bachelor's in Global Disease Biology and plans to start her career in health communications.