AB 617: Translating California’s dirty air into a cleaner bill of health

To help shore up California’s struggle for clean air, environmental advocates are championing Assembly Bill 617 (AB 617) to bring the fight more directly into the communities that shoulder a heavier burden when it comes to air pollution. To understand the need to improve California’s air, it’s key to dig into some of the state’s unique challenges.

Why is California's air so much worse than other states?

California is a major economic player with the fifth highest GDP in the world and a big producer of industrial pollution. The Golden State has the most Fortune 1,000 companies in the country with manufacturing, agriculture, technology and aerospace among its leading industries. Several of the country’s busiest ports on California’s coastline as well as the state’s many airports contribute to its bad air, with these sources emitting a range of criteria air pollutants linked to a variety of health problems.

Thriving industry creates jobs that attract a growing number of people making California the most populous state in the nation. More people means additional cars and trucks on California’s roads. The state has over 36 million registered automobiles, which is just about one car for each man, woman and child.

Chemicals from car exhaust and industrial pollution react to California’s sunny weather contributing to smog. Along with the state’s weak public transportation system which makes it difficult to get around without fossil fuels, there’s so much pollution that health officials continue to see worrying asthma rates among children despite increased regulation.

Now climate change is in the mix, making Californians face yet another threat to air quality. In what’s become an annual occurrence, urban wildfires are burning thousands of structures and filling the air with chemical clouds for weeks on end. California’s air quality is only expected to get worse with extreme heat and drought should global warming go unchecked.

California also is home to the Central Valley which has one of the world’s most significant geological depressions running through it. Mountains surround 20,000 square miles of flat, almost sea-level terrain. The Cascades to the north, Sierra Nevadas to the east, Tehachapi Mountains to the south and Coast Ranges to the west make the valley a perfect vessel for collecting air pollution.

How does air pollution affect health?

Although air quality in California has improved overall, it’s still at levels that are harming people’s health, and has taken a turn for the worse nationally since 2016.

Experts say that by reducing fine particulate matter to the lowest level of ambient (outdoor) air pollution, more than 7,200 premature deaths can be prevented in California each year.

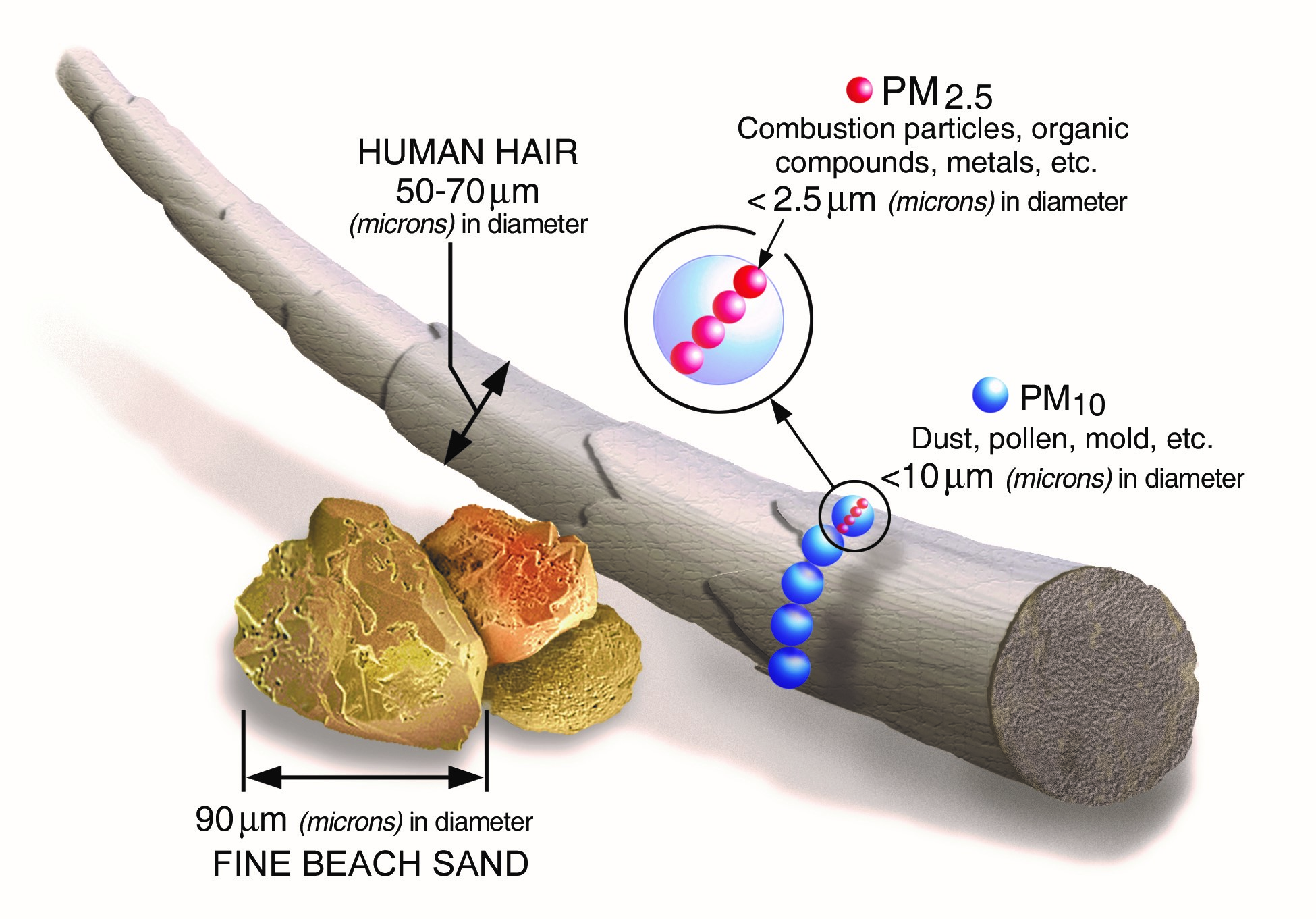

Air pollution is made up of fine particles, noxious gases, ground-level ozone and smoke. Health problems occur when inhaling particulate matter between 10 and 2.5 microns, the smaller of which is equivalent to about one-twentieth a diameter of a single strand of hair.

Due to their small size, these particles have an easy time entering the lungs. When inhaled, fine particulate matter is linked to a wide array of health problems including:

- Decreased lung function

- Irregular heartbeat

- Aggravated asthma

- Premature death in people with heart and lung disease

How is California addressing its air pollution problem?

California’s battle with air pollution dates back to the summer of 1943 when Los Angeles recorded its first episode of smog, which was so thick and made people so ill residents thought it came from a nearby chemical plant. In the 1950s, scientists linked smog to car pollution, and in 1967 the state created the California Air Resource Board (CARB).

California’s first big step toward improving air quality came when it implemented the first tailpipe emissions standards in the nation in the 1960s. Cars are now 99 percent cleaner compared with those in the 1970s. As a result, CARB says ozone levels have dropped more than 40 percent in Southern California since the 1990s, and the number of unhealthy ozone days has decreased 40 percent in the San Joaquin Valley. Levels of lead in the air are now 90 percent lower, and diesel particulate matter, which accounts for over two-thirds of the total known cancer risk from air pollution, has dropped nearly 70 percent statewide.

Today, CARB works with air districts to oversee air pollution and maintain health-based air quality standards across the state. CARB, an arm of the California Environmental Protection Agency (CalEPA), has a hand in tracking and analyzing hundreds of bills introduced in the state legislature each year. Its legislative work in shaping environmental policy covers the gamut from climate adaptation, low carbon innovation and coastal resilience to environmental farming, clean energy job creation, sustainable freight and much more.

Why is air pollution still a problem at the local level, and what is California doing about it?

Despite decades of regulations and improvements in air quality in California, significant health disparities persist. Communities overburdened by air pollution are the same communities that historically have been subject to discriminatory policies like redlining, highway construction and urban renewal projects, and in neighborhoods with limited access to health care, healthy food, quality education and outdoor spaces, all compounding the health burdens.

Despite decades of regulations and improvements in air quality in California, significant health disparities persist. Communities overburdened by air pollution are the same communities that historically have been subject to discriminatory policies like redlining, highway construction and urban renewal projects, and in neighborhoods with limited access to health care, healthy food, quality education and outdoor spaces, all compounding the health burdens.

Policy makers also have long overlooked these communities. Environmental justice (EJ) activists argue that the state’s cap-and-trade program – one of California’s signature environmental policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions – has allowed industry to continue to pollute these neighborhoods.

California’s top-down approach in addressing air pollution hasn’t helped local communities either. Power over air quality has been concentrated at the state and regional levels with authority to regulate coming from the federal Clean Air Act.

“The Clean Air Act is very specific about creating standards to regulate regional air pollution,” says Kevin Hamilton of the Central California Asthma Collaborative. “Defining what’s local is left up to the states and for almost 50 years has focused on air basin rather than local communities.”

But a shift from these approaches has percolated over the years, too. While the cost of local air monitoring has hampered the state’s ability to wholly address air pollution, technology has evolved and now a proliferation of cheap, off-the-shelf air monitors are available. At the same time, activists and experts say there’s been a realization that local air pollution might not be well represented by regional air monitoring. Meanwhile, communities left to advocate for themselves outside the official system of monitoring have been increasingly organized and vocal about the impact air pollution has had.

“When community-based organizations started doing community air monitoring by putting low cost sensors in areas where there weren’t regulatory monitors, data started showing another picture. There were hot spots,” says Nayamin Martinez, Director of the Central California Environmental Justice Network. Local groups started sharing their air pollution data and legislators like Eduardo Garcia began pushing for state intervention.

As all these forces coalesced, activists and policy makers came together to address the burden of air pollution in disadvantaged communities. The result was Assembly Bill 617 (AB 617), which Governor Jerry Brown signed in 2017. Since then, the state has poured almost half a billion dollars into cleaning up and mitigating air pollution at the local level.

AB 617: What does it aim to do?

The primary goal of AB 617 is to lessen the unequal burden of air pollution in communities across the state by partnering with locals to develop policies to clean up and prevent bad air.

“AB 617 builds on decades of clear air policies, and most recently a suite of environmental justice laws that prioritize overburdened communities for investments, enforcement, permitting and participation,” says Jonathan London, a professor at UC Davis and Director of the Center for Regional Change. The bill’s key components include:

- A uniform, statewide reporting system: The bill establishes a statewide system of annual reporting for non-vehicular air pollutants and toxic air contaminants.

- A statewide strategy that emphasizes local plans to reduce emissions: AB 617 sets up air monitoring plans and selection of high priority areas in need of air monitoring systems. It mandates a statewide strategy to reduce emissions, with a review at least once every five years. Through grants to community-based organizations, locals can more easily analyze data and participate in new air pollution reduction programs.

- Quicker review of pollution control technology. In districts exceeding air pollution limits, the new law supports an expedited process to implement the best available retrofit control technology at industrial sites.

- More significant penalties for polluters. Penalties increase five-fold to $5,000 for violating air pollution laws from non-vehicular sources.

How does the Community Air Protection Program work?

To implement AB 617, CARB created the Community Air Protection Program (CAPP). CAPP initiated eight actions to kick start its program.

1. Democratize participation. CAPP partners with community members through steering committees and grants to develop programs with air districts and CARB. Individual residents can participate in local steering committees, and meetings are open to the public. In the first round of funding, these grants ranged from $300 to $100,000 and helped local groups establish their own air monitoring networks, choose where monitors go and write their own emission reduction plans.

2. Take action statewide. CAPP is implementing new actions across the state to reduce emissions and public health impacts.

3. Support action locally: CAPP's community emission reduction programs (CERPs) are key to local action.

4. Track progress: CAPP creates accessible metrics for community members so they can track the progress of the program.

5. Develop resources wisely: By working with local land use and transportation agencies, CAPP aims to reduce air pollution sources located too close to residents.

6. Encourage green vehicle and equipment use: CAPP incentivizes businesses and communities to purchase greener vehicles and equipment.

7. Collect detailed reports: CAPP collects more detailed information on pollutants from air districts and community groups through new air monitoring programs.

8. Provide usable data. CAPP collects better data on air pollution sources and makes that information accessible and user-friendly.

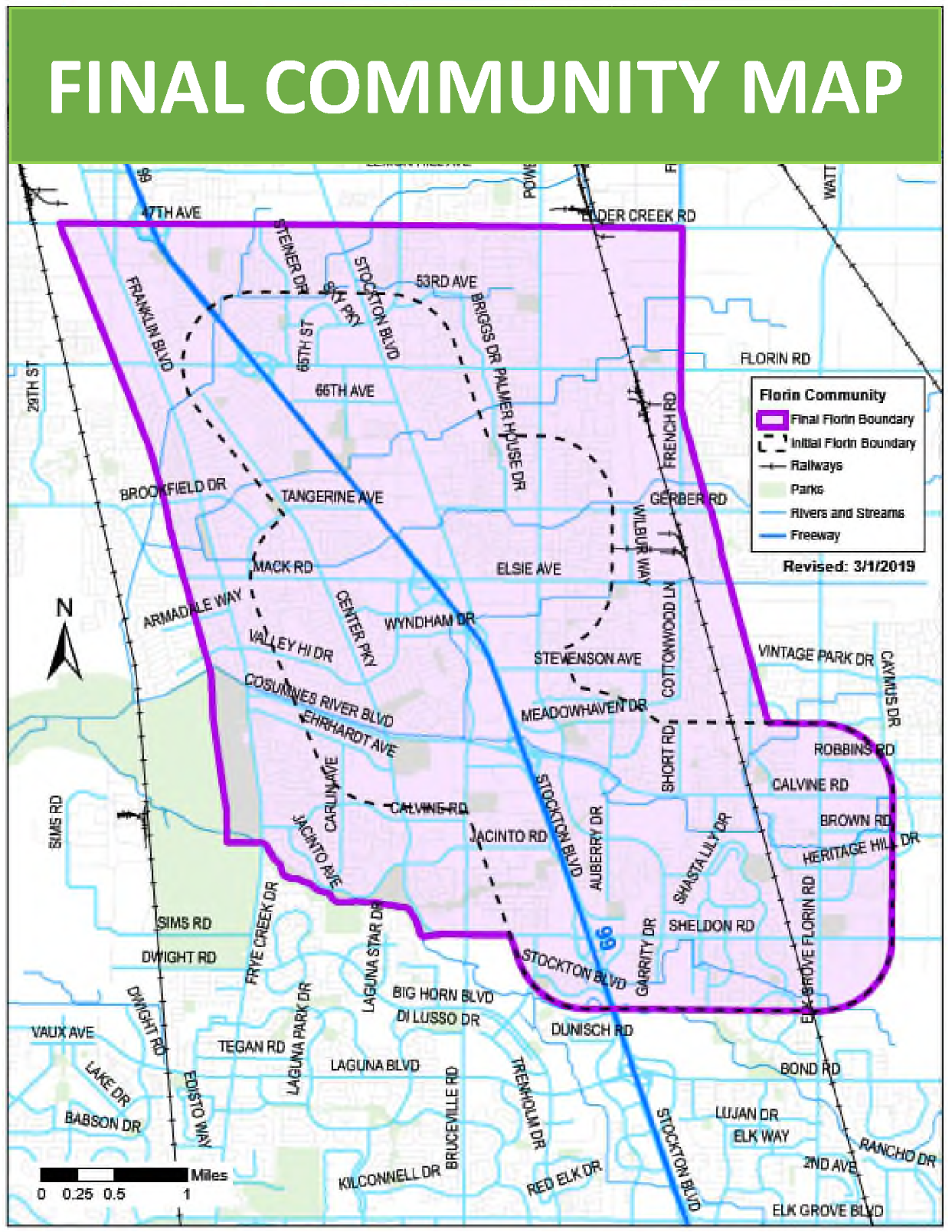

A little more than a year after signing AB 617, CARB selected 10 communities to begin working with CAPP. One of the selected communities for air monitoring technology was the South Sacramento- Florin neighborhood. The South Sacramento-Florin community has deployed monitoring systems that provide online real-time air quality data. This data will be used to establish future community programs to reduce pollution.

If all goes as planned, EJ activists hope to see cleaner air at the local level in these pilot communities within the coming decade.

What is the UC Davis Environmental Health Sciences Center doing around AB 617?

Many members of EHSC’s Community Stakeholder Advisory Committee have been an integral part of the creation and implementation of AB 617. Californians for Pesticide Reform, El Pueblo Para El Aire y Agua Limpia, Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice, the Central California Asthma Coalition and the Central California Environmental Justice Network are on the frontlines ensuring inclusion of pesticides in the legislation, deployments of community air sensors, community education around air quality and that those most in need of local air monitoring funds get it.

EHSC researchers have been directly involved too, including Community Engagement Core Co-Director Jonathan London who’s working with CARB to evaluate community-engagement efforts and locals to explore setting up Technical Advisory Groups with scientists who can provide independent assessments of monitoring plans and data.

EHSC researchers have been directly involved too, including Community Engagement Core Co-Director Jonathan London who’s working with CARB to evaluate community-engagement efforts and locals to explore setting up Technical Advisory Groups with scientists who can provide independent assessments of monitoring plans and data.

More broadly, EHSC serves as a vital link between EJ activists and scientists by bringing them together to share ideas and best practices, as well as by helping groups new to community air monitoring learn about the local work happening across the state.

“As small non-profits, we don’t have the capacity to pause, evaluate and see what the impact has been,” says Nayamin Martinez from the Central California Environmental Justice Network. “It’s important to have an objective perspective bringing us together and facilitating that exchange of information and lessons learned.”

Jennifer Biddle is a science and health writer, a longstanding member of the Association of Health Care Journalists and a Center for Health Journalism fellow. Her documentary Waking Up to Wildfires was nominated for an Emmy.

Jennifer Biddle is a science and health writer, a longstanding member of the Association of Health Care Journalists and a Center for Health Journalism fellow. Her documentary Waking Up to Wildfires was nominated for an Emmy.

Maddie Hunt is a former editorial assistant and budding science writer for the Environmental Health Sciences Center at UC Davis. She is a recent UC Davis graduate, with a Bachelor's in Global Disease Biology and plans to start her career in health communications.

Maddie Hunt is a former editorial assistant and budding science writer for the Environmental Health Sciences Center at UC Davis. She is a recent UC Davis graduate, with a Bachelor's in Global Disease Biology and plans to start her career in health communications.